|

| The Charge of the Light Brigade by Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. |

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, then the Poet Laureate of England got it exactly and

succinctly right when he wrote “Not

tho’ the soldier knew, someone had blunder’d... Charging an army, while all the

world wonder’d.” He dashed off what would become the recital piece of every English

schoolboy within moments of laying down the Times with a correspondent’s account of a disastrous vainglorious charge by

the British Light Cavalry into the teeth of Russian artillery that commanded

a long, narrow valley from the heights on both sides as well as the head of the vale. The poem, The Charge of the Light Brigade

was rushed to the press and

published on December 9, 1854, less than

six full weeks after the debacle.

|

| Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem fixed the story of the Light Brigade in the public imagination. |

One

could easily argue that not only was the charge itself an inexcusable blunder,

but so was the whole Crimean War of

which it became the most celebrated moment

of a wretched waste of lives and treasure. For arcane motives involving international imperial rivalries

particularly involving the Great Game

of Russian dreams of a deep water port on the Indian Ocean at the threat to British India and ambitions in Afghanistan,

former enemies Britain and France came to the defense of the Ottoman Empire

over Russians demands for protection of

Orthodox minorities in the Balkans.

Both

of the new allies had large armies

uniformed, armed, and drilled for

a Napoleonic Era war of massed formations and open country maneuver. Although the English in particular had

some experience with colonial warfare,

both main armies were more than rusty after

35 years of European peace and the

English in particular were commanded by inexperienced

and largely incompetent noblemen and wealthy gentry capable of buying

commissions. More over, the nature of modern warfare had changed

and no one was less prepared than the Western

powers. Principle innovations were vastly improved heavy and field artillery mounted

in unprecedented numbers, rifle-muskets that increased the accuracy of infantry

fire, and particularly the use of railroads

to supply and reinforce Russian forces through interior lines while the British and

French had a long and unreliable sea

connection.

After

inconclusive early action in the Balkans, the British and French decided to

attack the bastion Russian control

of the Black Sea, Sevastopol on the Crimean Penninsula. The Western armies had been rushed to the theater with only summer campaign uniforms, inadequate

tents and bedding, on short rations of barely edible bully beef. Moreover,

many were weakened by sickness

contracted on crowded troop transports

and once ashore were stricken by dysentery and infectious diseases.

Despite this, the British

and French had early success against

the ill-trained Russians after

landing unopposed on the Peninsula north of Sevastopol. But the Russians quickly fortified the city

and erected complex earthwork defenses which concentrated artillery fire

against possible attack. The war quickly

settled into a siege and the allies

were forced into miserable, water filled trenches opposite Russian

defenses. Staggering losses were soon

felt from Russian artillery pounding but especially from disease, exposure, and malnutrition.

|

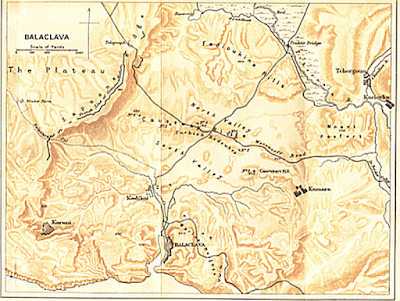

| A topographical map shows British held Balaclava and the valley between the Causeway Hills and the Fedukhin Heights into which the Light Brigade charged. |

To

break the situation open, the British launched a flanking amphibious maneuver, landing a substantial force east of Sevastopol at Balaclava. It should have been a masterful, war ending

operation. Instead a large Russian

Army began a counter-attack on the English toe hold beginning on October 23,

1853 which quickly routed Ottoman

forces occupying outer defenses on

the highlands around the port capturing

substantial Turkish artillery and turning it against the English. Although the English rallied in their

defensive interior trenches, the problem soon became how to re-capture or neutralize the former Ottoman guns.

The

British cavalry, which had missed earlier fighting as it was delayed at sea had arrived. It consisted of two divisions under the command of Lieutenant General George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan, who was under the overall orders of Field Marshal FitzRoy Somerset, 9th Earl of Raglin.

The

Heavy Brigade was mounted on chargers, wore silver helmets and

armored breast plates, and were armed with heavy

cavalry sabers. These men consisting

of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards,

the 5th Dragoon Guards, the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, and the Scots Greys were intended as heavy shock troops especially trained

for frontal assaults of artillery positions and capable of overwhelming them.

|

| Surviving officers and men of the 13th Light Dragoons at Balakava by James Fenton--one of the earliest war theater photographs. |

The

Light Brigade included the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons, 17th

Lancers, and the 8th and 11th Hussars, under the command of Major General James Brudenell, 7th Earl of

Cardigan. Lucan and Cardigan were brothers-in-law but also bitter service rivals who personally detested each other. This enmity

would have fateful consequences.

Raglin

recognized that the key to the upcoming campaign was re-capturing the Turkish

guns, mostly heavy naval rifles on

the heights. He intended for the fast moving Light Brigade to sweep around Russian flanks and attack

the guns before the Russians could evacuate

them and hopefully send the gunners into a panicked flight in which they could be hacked to pieces. It was

exactly the kind of work the light cavalry was designed for.

Raglin’s

written order to Lucan, drafted by Brigadier

Richard Airey read “Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to

the front, follow the enemy, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the

guns. Troop horse artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left.

Immediate.” This hasty and somewhat cryptic order

was carried to Lucan by Raglan’s favorite,

dashing young Captain Louis Edward

Nolan. Nolan was widely regarded as

the most outstanding and capable young officer in the Cavalry

with a great career and high command in his future.

Nolan

rode hard to find Lucan and

excitedly handed the commander his orders.

Lucan was somewhat mystified by the orders and asked Nolan, “What guns

does he mean?” Nolan replied with a casual sweep of his hand including not just the hills, but

the concentration of artillery at the head of the Valley. In fact Lucan assumed that he meant an

assault on those guns was the primary

objective.

Despite

the fact that such a charge was the purpose of the Heavy Cavalry under Major General James Yorke Scarlett,

Lucan believed the order was intended for Cardigan’s Light Brigade.

When

Cardigan received his orders to attack up the valley “without delay” he recognized that his units would be riding

into an unwinnable trap. He assumed his brother-in-law had issued the

order out of personal spite. But to uphold

his honor he decided to attack immediately without delaying for clarification of the orders from Raglan.

|

| A panoramic and fairly accurate depiction of the Light Brigade charge up the valley into the Russian guns from a popular late 19th Century print. |

With

Cardigan in the van, the 669 men of Light Brigade set off at a trot up the long valley between Fedyukhin Heights and the Causeway Heights. As a staff officer Nolan observed the maneuver

and expected Cardigan to quickly split his forces to the lest and right to

attack the heights. When instead they

picked up the pace to a full charge, a horrified Nolan rode around the troops

and across their entire front gesturing wildly and shouting “There’s been a

mistake!” until he was shot out of the

saddle and killed.

The

Heavy Brigade now under Lucan’s direct command, was held in reserve and was meant to follow on the Light Brigade when it breached the guns at valley’s

head.

The Russian

forces commanded by Pavel Liprandi

included approximately 20 battalions

of infantry supported by over 50 artillery pieces deployed on both

sides and at the opposite end of the valley.

Enfilading fire soon ripped

the ranks of the troopers from the heights while front was shredded by level fire heavy

with grape.

Despite

the heavy carnage, troopers reached the guns and sent the Russian artillerymen

into flight. But they were not able to hold on. Lucan, observing the disaster never launched his secondary attack with the Heavy Cavalry. The Light Brigade was put to flight and the Russian crews returned to their guns to pour

moved devastating volleys into their backs.

The

Light Brigade suffered horrendous losses of officers and men—110 killed

outright, 161 wounded, 60 captured and 335 horses

killed in action, or were put down after because of their wounds.

The

French light cavalry, the Chasseurs

d’Afrique under Armand-Octave-Marie

d’Allonville, did manage to clear

the Fedyukhin Heights of two half

batteries of guns, two infantry

battalions, and Cossacks and provided cover for the remaining elements of the Light Brigade

as they withdrew. The French Marshal Pierre Bosquet, famously observed of the Light Brigade sacrifice, “It is magnificent, but it

is not war, It is Madness!”

In

the end the soon to be world famous

battle had no immediate tactical or

long term strategic significance. The disorganized Russians, who had been

handed a gift beyond their expectations were

unable to take advantage of it and dislodge the British from Balakava. The Siege of Sevastopol settled into a long, nightmarish endurance contest that was

a preview of the trench warfare on the Western Front

during World War I.

The yearlong siege of Sevastopol killed

and wounded 170,000 men, on both sides not including the tens of thousands the

British and French lost to disease and ended when the Russians pulled off a near-miraculous evacuation of their

battered remaining forces over a pontoon

bridge. It signaled an ultimate

Russian defeat but was delayed by some minor, face saving victories by the Tsar’s troops in the Balkins. An Austrian ultimatum to Russia brought the

parties to the negotiating table where the British and French were ready to

grant none-to-terrible terms to end the whole bloody affair in March of

1856 with the Treaty of Paris.

No

one got much out of the bloodbath except

the Ottomans. The famously ailing Sick Man of Europe was able to limp along as the edges of its Empire were nibbled

away in rebellions and small

local wars until their involvement in the Great War brought down the

ancient Sultanate.

When

word of the disaster reached London in November, public reaction mirrored Tennyson’s, if not so elegantly expressed. The

troops were lauded—even idolized—as gallant heroes whose devotion

to duty and country against impossible odds were inspiring and unquestionable. The Army and government did everything in their power to encourage and spread this

sentiment. It was their armor against public outrage at the criminal

incompetence that led to the slaughter.

|

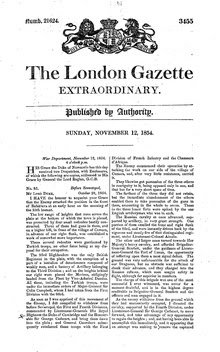

| London gets the news from Raglin's |

The

first report of the battle actually was printed in the The London Gazette in an “Extraordinary Edition” on November 12

and contained the official dispatches of

senior officers as addressed to the Secretary of State of State for War and the

Colonies Henry Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle. Raglin put the blame almost completely on

Lucan:

…from some

misconception of the order to advance, the Lieutenant-General (Lucan)

considered that he was bound to attack at all hazards, and he accordingly

ordered Major-General the Earl of Cardigan to move forward with the Light

Brigade.

Raglin

essentially claimed that whatever the orders he received, Lucan on the ground

should have exercised his discretion.

When

he learned that the official reports had been publicly exposed, Lucan wrote a

furious reply saying that Raglin had bound

him strictly to absolute obedience to

every order as issued. The War

Ministry blocked publication as a

breach of public decorum and disrespect to a senior officer. Lucan was recalled from duty and arrived in England in March 1854. But word

of his objections became public knowledge, if not the exact text of his defense. It was the beginning of

round-after-round of finger pointing and

blame shifting.

Meanwhile

William Russell of the Times,

the man who practically invented the roll of a professional war correspondent and would later notably cover major

campaigns in the American Civil War,

published his two lengthy accounts in December—the reports that inspired Tennyson’s

poem. None of the senior command escaped his blame except for Cardigan

who dutifully and valiantly executed his fateful orders

and did not receive the promised support of the Heavy Brigade. Cardigan was able to return home a hero and

was elevated over his superiors to Inspector

General of the Cavalry.

When

Lucan arrived in London in March he immediately launched what would today be

called a public relations offensive. He began with an exchange of letters the Times he reiterated his criticism of Raglin but also turned his sights on

Captain Nolan for delivering a garbled

message with unseemly agitated

excitement. Nolan was the perfect target. He may have been a promising officer but he was a junior

one without as yet a wide web of kin

and supporters at the upper

levels of the Army and government. He

was an Irishman with no aristocratic connections. Best yet, he was dead and unable to mount a defense.

Lucan

repeated his defense in a speech to a friendly

House of Lords. It worked like a charm. Lucan escaped further investigation or any

formal charges against him. Although he

never returned to active command, he was awarded the prestigious Order of the Bath that summer, made a

full General in 1865 and a superannuated Field Marshal in 1887, the year before

his death at age 88.

|

| Lord Raglin, the one-armed old soldier in over-all command in the Crimea died of dysentery and depression before he could come home. |

As

for Raglin, he remained in command in the Crimea overseeing the fruitless

stalemate. A botched piecemeal allied

assault on Sevastopol on June 18, 1855

was a complete failure was a complete failure.

The accounts of Florence

Nightingale and others held him responsible for the wretched condition of

his troops and their suffering. His own

health declined rapidly, accelerated by what is now recognized as clinical depression. He died, like so many of his men, of dysentery, just ten days after his

final blunder. His body was returned to

England to a solemn welcome and suitably grand funeral.

When

the survivors of the Light Brigade finally arrived home with the rest of the

battered Crimean army, their ranks further

thinned by subsequent actions and mostly by disease and exposure, they were

lionized. There were a number of

reunions over the years, most notably one in In October 1875 at the Alexandra Palace in London to celebrate

its 21st anniversary of the battle. It

was the largest event of its kind. The elderly

Lucan, probably unsure of his welcome, declined to attend but dined the same

night with some of his former officers.

In

1890 Rudyard Kippling wrote his own

piece about the Light Brigade portraying an apocryphal vistit to Tennyson by

the “twenty last survivors” begging him

to write a new poem to shame the British

public into offering financial

assistance to the elderly and neglected veterans.

Some

observers credit the glory bestowed on the Light Brigade for the mindset of sacrificial devotion to duty the led a generation of young Britons to their doom in fruitless over-the-top

bayonet charges into No Man’s Land in

the teeth of German machine guns and artillery. And as in the Crimea, incompetent but aristocratic

commanders usually escaped blame for the slaughter.

The

American Civil War helped popularize Tennyson’s poem in this country as an ode to battlefield gallantry. It was popular with troops on both sides, but

especially cherished by the plumed

knights of J.E.B. Stuart’s

Confederate Cavalry. In the post-war

years it became nearly as popular a school recital piece here as it did in

Britain.

|

| The Warner Bros.1936 version of the tale was mostly romantic fantasy showcasing their photogenic popular leads, Errol Flynn and Olivia DeHavilland, |

Most

Americans are only familiar with the battle through fragmentary memories of the

poem or from the highly inaccurate 1936

Warner Bros. historical romance, The

Charge of the Light Brigade starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de

Havilland. The movie portrayed the

charge as revenge for a massacre of Lancers at the hands of a Russian

influenced religious fanatic on the Northwest

Frontier of India. In the film Flynn

and his Indian Army troops are miraculously posted to the Light Brigade and the

villainous Surat Khan and his men

are manning the Russian guns. Flynn thus

portrayed heroic figures in two of the most famous military disasters of the 19th

Century including They

Died With Their Boots On about George

Armstrong Custer in 1941.

|

| The death of Captain Nolan, David Hemming, in the 1968 British film. |

Tony

Richardson’s 1968 British film, The Charge of the Light Brigade, a savage indictment of the stupidity of war and the British class system made at the height

of the Vietnam War era, was epic in scale, but contained elements of bitter

satire. I got the facts of the

debacle mostly straight. Little seen in

the U.S. it had a stellar cast of British film and theater notables including John Gielgud as Lord Raglin, Harry Andrews as Lord Lucan, Trevor Howard Lord Cardigan, and Richardson’s

wife, Vanessa Redgrave. David Hemming played Captain Nolan as

both a sympathetic naïve young man and a vainglorious twit, the perfect

scapegoat for the disaster. It was the most expensive British

film at the time it was shot but was a box

office failure when Richardson refused

to screen the film for critics

and went out of his way to insult and alienate them. In retrospect the neglected film has been

listed as one of the 100 Best War Films

of All Time in a 2004 British public

opinion poll.

It has been more than 50 years since that last

film. Many futile wars later, perhaps a new

version is in order. Too bad it

would probably be too expensive to make

and historical epics are out of fashion.

No comments:

Post a Comment